Confronting the Fragility of Existence

Friday, Mar 24, 2017 3:23:00 PM

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RLFVoEF2RI0

Meaning in Life and Work Calculators

Friday, Mar 24, 2017 3:24:00 PM

Dr. Steger constantly comes up in the Journal of Positive Psychology as one of the main meaning in life and work researchers. He made the questionnaires used for all the studies available for non-commercial use and I’ve converted them into free online calculators:

The Work and Meaning Inventory: https://kevgrig.github.io/wami-react/

The Meaning in Life Questionnaire: https://kevgrig.github.io/mlq-react/

Don’t Focus Just on Work Meaning

Saturday, Apr 01, 2017 3:23:00 PM

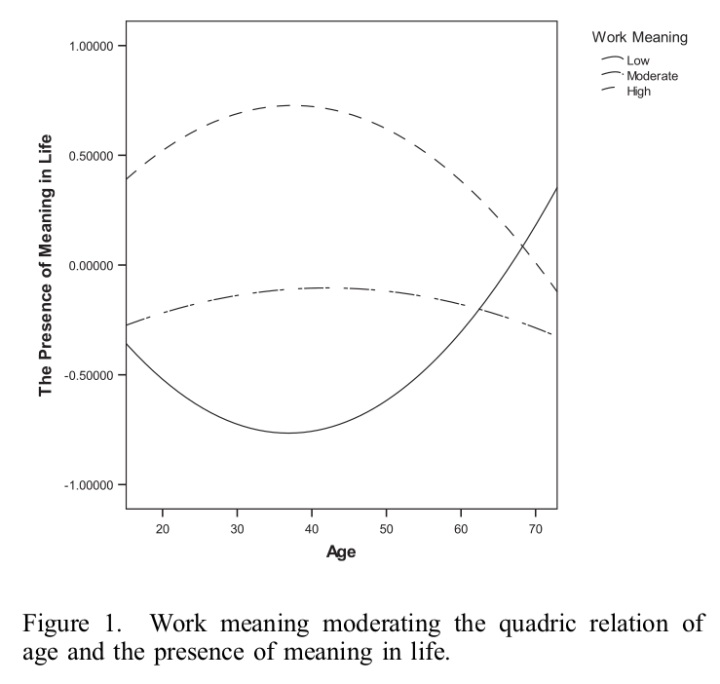

Allan et al 2015 seemed to find a fascinating correlation: those with moderate and high meaning at work ended up with lower and declining overall meaning towards the end of their life, as compared to those with low meaning at work ending up with higher and increasing meaning towards the end of their life:

Meaning in work refers to the subjective experience that one’s work has significance, facilitates personal growth, and contributes to the greater good (Steger et al., 2012). Conceptually, meaning in work is considered a sub-domain of meaning that acts as a potential source of meaning in life (Ebersole & DePaola, 2001; Emmons, 2003; Fegg et al., 2007; Steger & Dik, 2009). This is supported by several studies that have asked participants the sources of their life meaning, finding common responses including relationships, religion, service, and work (Baum & Stewart, 1990; DeVogler & Ebersole, 1981; Emmons, 2005; Fegg et al., 2007).

Following from this conceptualization, researchers have argued that experiencing meaning in work translates into greater meaning in life (Steger & Dik, 2009), an assertion supported by several studies showing that participants consistently report work as a major source of meaning (e.g. Fegg et al., 2007). Few studies have examined both life meaning and work meaning in the same study, but Duffy, Allan, Autin, and Bott (2013) found a correlation of 0.49 between the two variables in working adults. Several studies have also illustrated how well-being in the work domain can affect meaning in the life domain. For example, workaholism and work–life conflict are negatively associated with purpose in life, and work enjoyment is positively associated with purpose in life (Bonebright, Clay, & Ankenmann, 2000). Finally, adolescents who report purposeful career goals also report higher meaning in life (Yeager & Bundick, 2009). Therefore, there is some reason to suspect that meaning in work may translate into higher meaning in life. […]

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, individuals spend more time working on weekdays than any other life activity, including sleep (8.7 h a day; BLS, 2013). Therefore, it is not surprising that the meaning individuals experience at work would have a large effect on overall life meaning. What might be surprising, however, is the manner in which these two variables are related in different age groups. The relation of age and life meaning for individuals with low work meaning was U-shaped, with life meaning being low for individuals in their prototypical working years (ages 20–50) and adults over 50 reporting higher life meaning. An opposite pattern existed with individuals high in work meaning, with life meaning highest for those in their prototypical working years and lower for those over 50.

These results exemplify the role that the presence, or absence of, work meaning may play in promoting an overall sense of life meaning. For individuals high in work meaning, work may represent the dominant way one cultivates life meaning (Emmons, 2005; Steger et al., 2012). Subsequently, it may be that during these prototypical working years, people high in work meaning have plenty of opportunities to contribute to their life meaning through work. However, for both high and low work meaning groups, participants in their 60s experienced similar levels of life meaning. The reasons for this finding are largely speculative, but people in the second half of life may have more difficulty extracting meaning from work, which in turn may result in this group experiencing lower levels of life meaning. For example, the sources of meaning associated with work, such as recognition for achievement, meeting basic needs, and materialism, are lower in older adults (DeVogler & Ebersole, 1981; Prager, 1996), and some sources outside of work, such as maintaining values and religious practices, are higher during this period (Prager, 1996). Similarly, older adults may be less concerned with generative actions, which may be primarily preformed at work, so work might lose its potency to influence life meaning (McAdams et al., 1993). In either case, work meaning may be stronger for middle age and older adults, but the relation between work meaning and life meaning may be lower for older adults relative to those in middle age.

Contrary to people high in work meaning, those low in work meaning may not receive the same type of life meaning benefit from work. Therefore, for people with low work meaning in their prototypical working years, work might be taxing and uninteresting. Perhaps, working in a low work meaning job almost nine hours a day is a drain on overall life meaning. Intriguingly, life meaning was higher for individuals older than 50. Our data suggests that participants in their 60s (those high and low in work meaning) display relatively the same amount of life meaning. Like the high work meaning group, older adults low in work meaning may be more likely to find life meaning in other activities, perhaps as sources of meaning change during this time (Ebersole & DePaola, 2001; Prager, 1996). […]

As evidenced in our data, individuals highest in work meaning are the lowest in searching for life meaning. Work may be such an all-encompassing source of life meaning for individuals high in work meaning that the need to search for new sources is nonexistent. Older adults in particular may never have developed the motivation or skills to look for other sources of meaning. The finding that older adults that are low and high in work meaning have relatively the same level of life meaning life suggests that no matter how much work meaning an individual has, it may be important to be continually searching for other meaning sources. […]

[T]his study was cross sectional and examined separate individuals at different life time points. Doing so allowed the tracking of trends between variables and age, but it is impossible to make any claims about causality or the life track of specific individuals.

Meaning in life and work: A developmental perspective, B.A. Allan et al., The Journal of Positive Psychology, 2015, https://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2014.950180

Meaning In Life vs. Meaning Of Life

Wednesday, Apr 12, 2017 3:22:00 PM

Martela & Steger 2016 is the best overview I’ve found of the field of meaning research. From practical empirical results, to summaries of major themes and definitions, and all the way to discussions of Tolstoy, Camus, Socrates, and Plato, it’s an amazing and dense piece of research at only 11 pages long. If anyone’s interested in this field, start with this paper. The discussion about Tolstoy made me think that his book Confession, which I read last year, is probably what sparked my search for meaning (along with Huemer’s Ethical Intuitionism which rehabilitates the concept of meaning). Be careful what you read!

An initial step in understanding psychological research on meaning in life is to separate this question from the more philosophical question about meaning of life (Debats, Drost, & Hansen, 1995). This latter question looks at life and the universe as a whole and asks what, in general, is the point of life: Why does it exist, and what purpose does it serve? These kind of metaphysical questions are, however, ‘out of reach of modern objectivist scientific methodology’ (Debats et al., 1995, p. 359), and not questions for psychology to answer. The aim of psychological research on meaning in life is more modest. It aims to look at the subjective experiences of human beings and asks what makes them experience meaningfulness in their lives. […]

Meaning, as a word, comes from the Old High German word meinen, to have in mind (Klinger, 2012, p. 24). This already reveals that meaning is tied up with the unique capacity of human mind for reflective, linguistic thinking. […] When we ask what something means, we are trying to locate that something within our web of mental representations. Meaning is about mentally connecting things. This is true whether we ask about the meaning of a thing or the meaning of our life.

Meaning is thus about life as interpreted by a being capable of reflective thinking. While the question whether animals can experience pleasure and happiness has been debated within science at least since Darwin (1872; see also McMillan, 2005), we are aware of no serious argument for animals experiencing a sense of meaning in life. Meaning, at least in its more developed forms, is thus an exclusively human affair. […]

[T]here are three basic facets of this search for meaning in life, corresponding to three different domains of human experience: coherent understanding (cognitive), worthwhile pursuing (motivational), and valuing living (evaluative). Meaning is about rising above the merely passive experiencing, to a reflective level that allows one to examine one’s life as a whole, making sense of it, infusing direction into it, and finding value in it.

The three meanings of meaning in life: Distinguishing coherence, purpose, and significance, Martela & Steger, The Journal of Positive Psychology, 2016, https://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2015.1137623

Randomized Controlled Trial on Pro-social Behavior and Meaning

Tuesday, Apr 25, 2017 3:22:00 PM

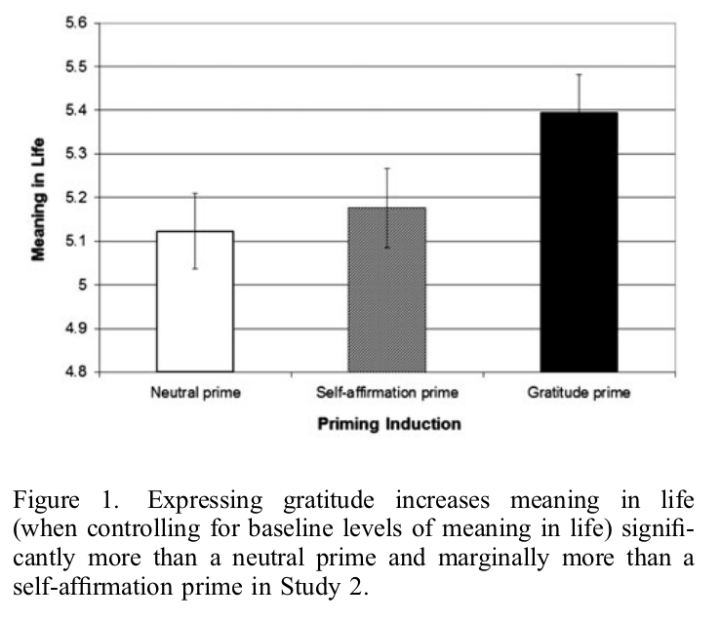

The results of Study 2 provide the first experimental evidence to our knowledge that engaging in the prosocial act of writing gratitude notes enhances meaning in life. Participants assigned to write short notes of gratitude [(5–10 min writing short notes of gratitude to (up to) four people who have positively influenced their lives)] reported [5%] greater meaning in life (while statistically controlling for baseline levels of meaning) after expressing this prosocial behavior than participants in a neutral priming condition and marginally more than participants in the self-affirmation condition. Conversely, the self-affirmation prime did not increase meaning in life relative to the neutral condition. This provides additional evidence for the meaning provision hypothesis: prosocial actions are a source of meaning in life, and the results are not simply due to prosocial behaviors being self-affirming or solely a function of positive mood. […]

[W]e suspect that acting antisocially does not necessarily translate to lower meaning in life. Individual perceptions of meaning in life are necessarily subjective, and individuals derive meaning from various sources in life (see Heine et al., 2006; Wong, 1998). The results here suggest that prosocial behavior is one potential source of meaning. […] We further emphasize that prosocial behavior is but one way to procure meaning in life. There are other ways in which individuals can find meaning (e.g. having a successful career, cultivating a garden) that are not directly relevant to prosociality.

Prosociality enhances meaning in life, Tongeren et al, The Journal of Positive Psychology, 2016, https://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2015.1048814

Next 5 Previous 5