What if I’m deluded?

Wednesday, Mar 01, 2017 4:27:00 PM

I think it’s always healthy to consider every criticism. As I research meaning, I’ll use this post to track every criticism I find and my self-analysis. Some are plausible, some probably apply to many people, and some seem like baseless pop-psychology. It’ll be useful to periodically review this list to make sure I’m not falling into any traps.

-

Trap: Trying to find meaning is just a proxy for an in-born need for social stability.

But because man, out of need and boredom, wants to exist socially, herd-fashion, he requires a peace pact and he endeavors to banish at least the very crudest [war of all against all] from his world. This peace pact brings with it something that looks like the first step toward the attainment of this enigmatic urge for truth. (Nietzsche)

Trap: Trying to find meaning is a coping mechanism or rationalization for failure.

Trap: Trying to find meaning is an existential crisis in the face of an impending death.

Trap: Trying to find meaning is pointless but people associate an undue importance with it because it’s such a difficult (or impossible) task.

Trap: Deciding on what is meaningful is mired in potential cognitive dissonance.

Trap: Interventions not based on precise understanding are likely to do more harm than good.

Trap: There is no such thing as objective meaning.

Trap: Ideas of meaning are psychological delusions used to enhance survival that are the result of millions of years of evolutionary biology.

-

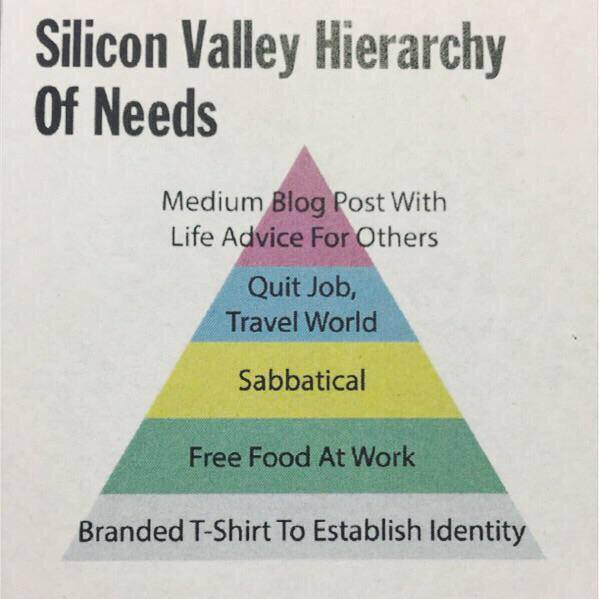

Trap: Displacing a serious struggle with distractions and delusions as depicted by this sarcastic Maslow hierarchy:

- My thoughts: This is certainly possible; however, I’ve avoided the “travel the world” trope, but maybe that’s because I already did that for ten years as part of my job? Also, I certainly didn’t mean for this blog to come off as advice to others, but it’s worth exploring my need to share my journey even though I know from past experiences that most people that I invited to follow this will likely contribute little. I can say that I made a conscious decision to exclude certain people (most of my contacts) from my initial email because I thought they might take this the wrong way, so that’s some evidence that this doesn’t come from narcissism.

-

Trap: Quitting and writing a blog are just the luxuries of a spoiled, rich, lazy, and decadent boredom.

- My thoughts: This is certainly possible; however, I seem to be struggling and wrestling with the questions, but I must admit I’ve indulged in some selfish pursuits at the same time. It certainly doesn’t feel like a life-or-death struggle, but why should it? Maybe after a certain amount of wealth, cleaning up the psyche, and healthy friendships and hobbies, Maslow’s self-actualization is simply the next step?

-

Trap: From an evolutionary biology point-of-view, perhaps being male — a sort-of mutated female — requires a pseudo-child to bear (e.g. “my work is my baby”) in the form of self-actualization.

- My thoughts: Need some evidence and primary sources on this to evaluate further; otherwise, might just be pop-psychology.

-

Trap: The search for meaning is an over-intellectualization of being burned out and needing a vacation.

- My thoughts: This is certainly possible; however, I enjoyed working until the last day (and even helped some colleagues a bit, for no pay, after leaving), and I didn’t feel burned out. I did spend the first few weeks mostly just sleeping, but that felt to me like a luxury of freedom that I worked hard for 15 years for, rather than being burned out.

-

Trap: This is just because you don’t have a family, children, and/or other major responsibilities.

- My thoughts: The latter part of this is true for me right now. I imagine a bright future with family, children, and other major responsibilities and Baumeister et al 2013 suggests that these are contributors to meaning, but it’s unclear to me that this answer is necessarily so simple, and it disregards Frankl’s argument. This argument and the search for meaning do not seem mutually exclusive to me, and there’s a converse trap of using this argument (or hedonism, drugs, etc.) as an excuse instead of finding meaning (e.g. no time, too much stress, etc.).

Trap: You can’t accomplish much that’s meaningful without money, power, social network effects, health, free time, friends, etc.

Trap: Discovering or even understanding meaning is hopeless.

Trap: The search for meaning does not appear to lead to its presence.

Trap: The search for meaning is broken.

Trap: Homo Sapiens are story-telling animals and we expect the same for meaning. “Reality doesn’t come in the shape of a story. […] It’s a human invention. And how to overcome that, I don’t think we are anywhere near knowing the answer to that one.”

Trap: Asking about meaning is a category error.

Trap: Searching for meaning is a depressive reaction to feeling threatened or helpless.

Trap: It’s hard to finding meaning because it’s hard to act in the world in a non-Hayekian way.

Trap: Meanings are made in sub-cultures.

Trap: Creating meaning is a collaborative activity.

Trap: The urge for meaning is an unending distraction for societal happiness at the expense of private happiness. An alternative would be some sort of pastoral Epicureanism.

Trap: The search for meaning is a drive to attempt to climb the dominance hierarchy by acting out the hero myth.

Trap: Meaning is within a a nearly impossible to understand chasm between the subjective and the objective.

Trap: The search for meaning is a surrogate activity directed towards artificial goals to compensate for the meaning-crushing nature of the modern world.

I welcome all other criticisms.

Nihilism and Meaning

Sunday, Mar 05, 2017 4:26:00 PM

Although I’m nauseatingly disgusted by Nihilism, French Existentialism, and Scientism, and my Bayesian prior is that they’re wrong or incomplete, I can’t deny their plausibility. However, from what I’ve read, these philosophies usually deny objective meaning in very sloppy ways, so I was pleased to find A Nihilist’s Guide to Meaning, which struggles with meaning at some depth:

I’ve never been plagued by the big existential questions. You know, like What’s my purpose? or What does it all mean? […]

Unfortunately, some of my favorite writers of recent years — Sarah Perry and David Chapman, in particular — can’t seem to shut up about meaning. […] I’ve long struggled to make heads or tails of such metaphors — and yet these are solid, STEM-y thinkers, people I trust not to take me too far off the rails. […]

I’d like to venture a more explicit hypothesis about what, exactly, underlies our perceptions of meaning. Please forgive the mathy tone here:

A thing X will be perceived as meaningful in context C to the extent that it’s connected to other meaningful things in C.

Sarah gives a helpful metaphor: meaning is pointing. So the more arrows issuing out from something, the greater its meaning. […]

If meaning is about connectedness, and especially causal influence, we can see why it’s adaptive to pursue meaning. Perceptions of meaning allow us to answer a question we’re always asking ourselves, “Why am I bothering to do this?” If an activity feels meaningful, it merits our continued attention and investment. Whereas if it feels meaningless, an appropriate response is to stop doing it — to give up and search for a more meaningful path. To seek meaning, then, helps us avoid dead-ends and retain control over our lives. Just as boredom and ennui are emotions that prompt us to make better use of our time or to look for other opportunities, our perceptions of meaning (or lack thereof) prompt us to think about the deepest, longest-term impact of our actions, and to steer toward better outcomes.

It’s important to remember, though, that we can get duped into perceiving meaning where it doesn’t actually exist. As in many other areas of life, we can’t always pursue the outcomes we want directly. Instead we evolved to pursue a set of cues that give us the subjective sense of meaning. These cues typically correlate with real meaning, but have the potential to lead us astray, and in clever hands can even be used to exploit us. A charismatic CEO, for example, waxing grand and eloquent about the company’s mission, can create a strong sense of meaning in his employees — but all too often it’s illusory, the reality less “world-changing” than the rhetoric. […]

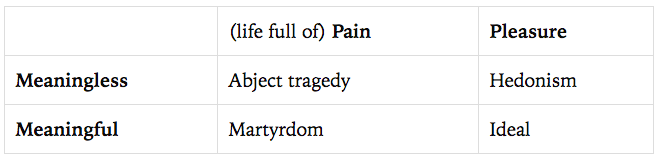

One of the best ways to look at meaning is to contrast it with pleasure. Consider this dramatically oversimplified formula:

Life satisfaction = pleasure + meaning

“Pleasure” here is what hedonists traditionally try to maximize. It includes health, comfort, and all manner of enjoyable sensory, aesthetic, and cognitive experiences, along with the absence of pain, misery, and suffering. Even beauty, for the hedonist, gets rolled up into the pleasure term.

Now we could imagine defining “pleasure” in such a way as to include “meaning.” After all, it feels good to experience meaning in one’s life. So why break meaning out into its own separate term?

One reason is to highlight how people are often forced to choose between meaning and pleasure; the two experiences seem to trade off against each other in interesting ways. Having children, for example, seems to reduce one’s pleasure, at least in the short run, while contributing greatly to one’s sense of meaning. (More here.) In the extreme case, martyrs are willing to endure torture and die for the sake of something larger than themselves. And sure, a martyr is a tragic figure — but vastly more tragic is he who suffers and dies for no purpose whatsoever:

But the bigger reason to separate meaning from pleasure is that pleasure is a strictly subjective experience. You can close your eyes and bliss out as hard as you like, and the pleasure you experience will be no less valid because it’s “just in your mind.” Meaning, on the other hand, is entangled with external reality, making it possible to be wrong about it. And thus the pursuit of true meaning requires an outward orientation to the world.

Meaning vs. Purpose (in Cancer Patients)

Monday, Mar 20, 2017 3:25:00 PM

George & Park 2013 surveyed cancer patients (twice, one year apart) with questions about meaning and purpose, and tried to tease out any potential differences. Meaning seems to be related to making sense of the why’s and what-for’s of life (e.g. religion/spirituality, etc.), whereas purpose seems to be related to accomplishing goals (e.g. direction in life, optimism, social support, etc.).

In the past few decades, the constructs of meaning and purpose have received increased scholarly attention and have come to be viewed as fundamental to wellness and fulfillment […] Empirical research has substantiated theoretical claims that a sense of meaning and purpose in life are important to well-being.

[T]he current study conceptualizes meaning and purpose as distinct constructs. Meaning is conceptualized as the subjective experience of perceiving life as fitting into a larger context and finding significance in it (Yalom, 1980). Individuals experiencing meaning are able to feel a sense of comprehension and significance in their lives and feel that life as a whole “makes sense” (Baumeister, 1991). In contrast, purpose is the subjective experience of possessing a system of overarching goals that provide a sense of direction in life (McKnight & Kashdan, 2009). Purposeful individuals have an attitude towards the future characterized by a sense of enthusiasm and excitement. They see the future as promising and their current actions as leading to such a positive future state. […]

There is evidence to suggest that the term meaning represents more than merely a sense of goals, aims, and direction for individuals. For example, Wong (1998) asked lay people to describe their conceptions of an ‘ideally meaningful life.’ Participants’ descriptions consisted of a whole host of topics that are distinct from what we refer to here as purpose – participants wrote about having religious beliefs, intimate relationships, a sense of transcendence, being treated fairly, and living life in fulfilling ways. Therefore, when the term meaning is being used, people seem to think beyond mere goals and a sense of direction. […]

However, although they are closely related, the presence of one may not guarantee the other. For example, an individual who is concerned with climbing the career ladder may generate a system of goals and hence possess a strong sense of purpose, but these goals may or may not in turn contribute to a sense of comprehension and understanding regarding life (i.e. meaning). […]

We examine these questions in a sample of cancer survivors, as questions of meaning and purpose are particularly salient for individuals dealing with crises. […]

Meaning and purpose were strongly correlated (r = 0.61, p < 0.01). […]

Given that meaning and purpose were substantially correlated with one another, partial correlations were conducted to tease out the psychosocial predictors of each, controlling for the other. […]

[P]artial correlations showed that Time 2 meaning was positively related to Time 1 religiousness and spirituality (whereas Time 2 purpose was not). Religion and spirituality offer comprehensive frameworks to understand and comprehend one’s existence and thus provide meaning (Park, 2005; Silberman, 2005). As this is a more salient function of religiousness and spirituality than the provision of a sense of goals and enthusiasm and excitement regarding the future, it is to be expected that religion and spirituality would be more closely associated with meaning than with purpose (Park, 2013; Park et al., 2013). Also consistent with the idea that comprehension and significance are more defining of meaning than purpose were the partial correlations that showed a positive relationship between Time 2 posttraumatic growth and Time 2 meaning and a negative relationship between Time 2 posttraumatic depreciation and Time 2 meaning. […] After an experience of crisis, individuals struggle to make sense of their experience, and to incorporate their experience into their worldview (Janoff-Bulman, 1992; Park, 2010). This process may be accompanied by growth in various aspects of their lives (Tedeschi & Calhoun, 1996) as it allows individuals to make sense of their experience and gain a sense of significance regarding the event and their lives (Janoff-Bulman & Yopyk, 2004). Posttraumatic growth helps individuals answer fundamental questions regarding the experience such as ‘why did it happen?’ and ‘what for?’ (Davis et al., 1998). Similarly, posttraumatic depreciation may hinder participants’ ability to make sense of their experience and thus lower meaning. In our sample, individuals who perceived more growth following their cancer diagnosis had a greater sense of meaning and those who perceived more depreciation had a lower sense of meaning, supporting the idea that part of meaning is the ability to make sense of one’s life and life events.

Consistent with the definition of purpose as a sense of goals, direction, and enthusiasm regarding the future, partial correlations showed that Time 2 purpose was positively associated with Time 1 optimism and negatively associated with Time 1 pessimism. […] It seems that in our sample, individuals who had more positive expectations of the future (optimists) also experienced more purpose in life. Furthermore, Time 1 goal violations pertaining to cancer were also inversely predictive of Time 2 purpose (but not of Time 2 meaning). Survivors who perceived their cancer experience as violating their goals perceived less purpose one year later, supporting the idea that goals are more central to the experience of purpose than of meaning. […]

For Time 2 meaning, Time 1 spirituality emerged as a unique predictor. The spirituality measure that we used captured subjects’ perception of the transcendent (God, the divine) in daily life and the degree to which s/he feels involved with the transcendent (Underwood & Teresi, 2002). The fact that experiencing the transcendent uniquely predicts meaning is consistent with the idea that meaning refers to a sense of understanding and significance regarding life. In contrast to meaning, regression results showed that Time 2 purpose was uniquely predicted by Time 1 interpersonal support and marginally (inversely) predicted by pessimism. The marginally significant inverse prediction of purpose by pessimism is consistent with the definition of purpose as a sense of goals, direction in life, and enthusiasm regarding the future. Pessimists have generalized expectations regarding outcomes that are negative (Scheier & Carver, 1985). Individuals with such negative expectations perceive more difficulties regarding their goals and more readily disengage from them (Carver & Scheier, 2002). Such a scenario is likely to result in a lower sense of purpose.

Some of the results were inconsistent with our expectations. The fact that regression analyses showed interpersonal support as a unique predictor of purpose but not of meaning was surprising considering that social relations are a primary source of meaning in individuals’ lives (Debats, 1999; Wong, 1998). Close relationships can add a sense of value and significance to one’s existence and make people feel that life is worth living (Yalom, 1980). […]

Another finding that was inconsistent with our expectations was the lack of a relationship between Time 2 meaning and Time 1 belief violations pertaining to the

cancer diagnosis. As core beliefs help individuals comprehend and understand their experiences (Janoff-Bulman, 1992; Koltko-Rivera, 2004; Park, 2010), we expected a negative relationship between belief violations and meaning. […]An intriguing aspect of our results was the set of relationships between meaning and purpose and crises. On the one hand, Time 2 posttraumatic growth and posttraumatic depreciation following one’s cancer diagnosis was correlated with Time 2 meaning but not with Time 2 purpose. On the other hand, Time 2 intrusive thoughts pertaining to the cancer experience was correlated with Time 2 purpose but not with Time 2 meaning. Lifetime incidence of crises measured at Time 1 also negatively correlated with Time 2 purpose but not with Time 2 meaning. This begs the question, are crises and the consequences of crises related more to meaning or to purpose? […]

Our analyses also showed that meaning and purpose were not related to demographic variables such as socioeconomic status and level of education. Socioeconomic status and level of education have been associated with purpose in the past (Ryff & Singer, 2008). Higher economic opportunities and educational standing may allow individuals to pursue personally valued goals and paths and thus confer an increased sense of purpose (Ryff & Singer, 2008). One possibility as to why we did not find a similar relationship is that the diagnosis of cancer may have affected this relationship. Crises and other difficult experiences could cause changes in sources of meaning and purpose (Tedeschi & Calhoun, 1996). They could result in the discovery and commitment to meaningful and purposive aspects of one’s life regardless of one’s life circumstances (Frankl, 1963) – aspects which transcend the material realm and that are less dictated by socioeconomic and educational standing (e.g. spiritual beliefs and social connections). From an existential standpoint, the experience of cancer may put individuals on an ‘equal playing field,’ and this may explain why we did not find a relationship between meaning and purpose and socioeconomic status.

Are meaning and purpose distinct? An examination of correlates and predictors, Login S. George & Crystal L. Park, The Journal of Positive Psychology, 2013, https://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2013.805801

Pitfalls of Meaning Research

Wednesday, Mar 22, 2017 3:24:00 PM

Park & George 2013 find that research on meaning appears to be in its infancy:

Many studies have found that searching for meaning is related to less distress (e.g. Davis, Nolen-Hoeksema, & Larson, 1998; Sears, Stanton, & Danoff-Burg, 2003), while others have found it to be related to higher levels of distress and dysfunction (e.g. Bonanno, Papa, Lalande, Zhang, & Noll, 2005; see Park, 2010, for a review; Roberts, Lepore, & Helgeson, 2006). In addition, there is little evidence that meaning making results in meanings made (e.g. Kernan & Lepore, 2009; McIntosh, Silver, & Wortman, 1993; Thompson, 1991).

Inconsistent findings regarding the meaning-making framework are not surprising given the tremendous variations in design and measurement across studies. […] [I]nadequate measurement greatly constrains current knowledge of meaning making. […]

A recent review of measures of meaning in life identified nearly 60 measures (Brandstätter, Baumann, Borasio, & Fegg, 2012). This abundance reflects the complexities involved in defining and measuring individuals’ subjective sense of meaning. […]

In the past, popular meaning measures such as the Purpose in Life Test (Crumbaugh & Maholick, 1964) have been criticized for having items that are confounded with positive affect and life satisfaction (Dyck, 1987; Yalom, 1980). Many of these problems persist in currently used measures. […]

Because there is as yet little consensus on exactly how meaning making occurs or of what it consists, approaches to assessing meaning making remain somewhat diffuse. […]

Many studies have assessed meaning making by simply asking participants if they have been searching for meaning or trying to make sense of the stressful situation (e.g. Holland, Currier, & Neimeyer, 2006). As noted in Table 2, these measures are problematic in that they lack established validity beyond face validity, and research suggests that people interpret these items in extremely different ways (e.g. Wright, Crawford, & Sebastian, 2007). […]

Similar to meaning making, many researchers have adopted a fairly simple approach to determining whether meaning has been made, essentially asking the respondent whether he or she has ‘made meaning’ from the event. This question, like its meaning-making counterpart described above, appears to lack any validity beyond simple face validity. […]

The meaning-making literature is replete with examples of the same construct being defined in different ways, and distinct constructs being used interchangeably (see Park, 2010 for a review). This has resulted in confusion and mischaracterizations of findings. […]

Often, meaning making is operationalized via questions that ask participants if they have been searching for meaning […] The wording of such items may make a large difference. For example, in one study, responses of mothers with children undergoing bone marrow transplantation to items such as ‘searching for meaning’ and ‘searching for positive meaning’ were not correlated (Wu et al., 2008). Therefore, researchers need to carefully choose measures that have demonstrated validity and ensure that the measures adequately tap the constructs that they are intended to assess. […]

The majority of existing studies on meaning making have used cross-sectional designs. Cross-sectional designs are limited as they do not capture changes in meaning over time and provide little information regarding the interplay among stressors and components of the meaning making framework. Prospective, longitudinal research designs are crucial in this regard as they capture the dynamic processes underlying meaning making. Although longitudinal and prospective studies can be challenging, they are feasible (e.g. studying high risk populations; Bonanno, Wortman, & Nesse, 2004). […] Although this approach has seldom been employed as a way of examining shifts in these important aspects of meaning over time, results of studies that have employed this approach suggest that it is a very fruitful way to study meanings made over time (e.g. Park et al., 2008). For example, one study of diabetes, heart failure, and asthma patients found that reductions over time in the extent to which their illness was appraised as hindering their goals predicted later improved quality of life (Kuijer & De Ridder, 2003). […]

Most existing studies have focused on small parts of the meaning-making model, precluding a full test (see Park, 2010, for a review). These approaches render the drawing of conclusions difficult. For example, researchers looking to study the relationship between meaning making and adjustment often assess meaning-making efforts without assessing meanings made (e.g. DuHamel et al., 2004). Without assessing meanings made, it is impossible to differentiate between successful meaning making and maladaptive ruminations, and the question of whether meaning making is related to positive adjustment remains unanswered. Similarly, some researchers assess current beliefs without assessing what beliefs were like pre-trauma (e.g. Foaet al., 1999). This approach provides little information regarding changes in beliefs, which is a crucial part of the meaning-making process. […]

Although meaning and meaning making are widely considered to be crucial to individuals’ adjustment to stressors (Davis et al., 2000; Gillies & Neimeyer, 2006; Janoff-Bulman, 1989, 1992), empirical research to date has not been able to confirm these theoretical propositions and provide a thorough understanding of meaning making (Park, 2010). Methodological limitations, inadequate measurement, and the lack of a standard model of meaning making are largely responsible for this lack of definitive research.

Assessing meaning and meaning making in the context of stressful life events: Measurement tools and approaches, Crystal L. Park and Login S. George, The Journal of Positive Psychology, 2013, https://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2013.830762

Presence-of vs. Search-for Meaning (in Prisoners)

Wednesday, Mar 22, 2017 3:25:00 PM

Vanhooren et al 2016 interviewed prisoners and found that a feeling of the presence of meaning versus the search for meaning seem to be distinct mindsets. The presence of meaning is associated with well-being, low distress, and better health, but the emotions associated with the search for meaning are mixed – sometimes openness and curiosity, but other times rumination and depression. Part of the breakthrough for some prisoners was being “seen” and “believed in” by others. This capacity for change appears to be partly forged in childhood, creating or depressing a sense of the potential meaningfulness of the world.

Martha, a 57-year old-female prisoner, had been incarcerated for 15 years. Reflecting on her prison experiences, Martha explained how she struggled with feelings of hopelessness. In her daily solitude she fought against the temptation to commit suicide. One of the things that kept her going was her personal knitting project. With the help of a chaplain her knitted bunnies were sold outside prison and the profit went entirely to an orphanage in Eastern Europe. Martha strongly asserted that as long as she could mean something to another person, life was still worth living. […]

In general, presence of meaning has been defined as an individual’s perception of his or her life being significant, purposeful, and valuable (Steger, Frazier, Oisgi, & Kaler, 2006). People experience meaning when they comprehend the world, when they understand their place in it, and can identify what they want to accomplish in life (Steger, Kashdan, Sullivan, & Lorentz, 2008). […]

Higher levels of presence of meaning have frequently been associated with positive well-being, lower levels of distress, and better health outcomes (for an overview, see Steger, 2012). The links between the search for meaning and well-being have been less clear (Steger, 2013). Some studies found a search for meaning to be related to a lower level of well-being whereas other studies yielded mixed results (Steger, 2013). Steger et al. (2008) discovered that searching for meaning was not only related to rumination and depression, but also to openness and curiosity. […]

Maruna (2001) analyzed the narratives of interviews conducted with 50 ex-prisoners. The main purpose of this research was to study differences between offenders who successfully desisted from crime and offenders who persisted in crime. Remarkably, no differences were found in their socio-demographic background, in their crimes, the amount of committed crimes, or in their personality structure. One of the main differences between desisting and persisting offenders was the fact that they showed distinct profiles vis-à-vis meaning. Interestingly, persistent offenders were not likely to search for meaning. Maruna (2001) described their experience of meaning in life as ‘empty’ and self-centered. Their life purposes reflected this emptiness through the pursuit of hedonic happiness, such as hyper-consumption and sensorial thrills. This group avoided making life choices and taking responsibility for their own lives.

Meaning in the desisting group, however, was marked by a search for meaning, and the desire to accomplish self-transcending purposes, to contribute to larger causes, and to care for others (e.g. volunteer work). This group had also experienced emptiness in the past, but their experience of meaning had changed, primarily caused by the fact that they had an experience in which someone ‘believed’ in them. The experience of being ‘seen’ by another person and being truly valued prompted the onset of a profound process of change. This process involved an internal search for meaning, during which their inner sense of self and their purpose in life were recalibrated. As a result they experienced a higher sense of meaning in life, which was accompanied by higher levels of self-worth and the belief that they could change their destiny.

In the general population, self-worth has been found to be an important source of meaning (Baumeister, 1991). Connectedness with others is also found to be closely linked with feelings of meaningfulness (Stillman et al., 2009). A recent study on sources of meaning discovered that adults in the Western world especially derive meaning from personal growth and family involvement (Delle Fave, Brdar, Wissing, & Vella-Brodrick, 2013). The connection between people’s experience of meaning, their sense of worth, their perception of others and the world has been studied closely by Janoff-Bulman (1992). Janoff-Bulman (1992) and Park (2010) argue that people’s experience of meaning is usually built upon

assumptions about the self, others, and the world, which form their personal meaning system. These assumptions are basic schemes through which individuals understand or give meaning to themselves and to the world. Schemes like these are usually shaped during childhood and most people seem to develop positive assumptions about life. More specifically, people usually have a positive sense of self, and they experience the world as mostly benevolent and meaningful (Janoff-Bulman, 1992). […]Several studies discovered that a vast majority of the prison population is raised in highly stressful environments, with a high occurrence of child abuse, neglect, and violence (Gibson, 2011; Grella, Lovinger, & Warda, 2013; Harner & Riley, 2013). In a pilot study with young prisoners (N = 38), the World Assumption Scale (WAS) (Janoff-Bulman, 1989) was used to measure three central world assumptions: self-worth, perceived benevolence of others, and the meaningfulness of the world (Maschi, MacMillan, Morgen, Gibson, & Stimmel, 2010). Cumulative trauma prior to imprisonment was significantly correlated with lower scores on the WAS, and most specifically with rather negative assumptions about the meaningfulness of the world (Maschi et al., 2010). This relationship was confirmed in another sample (N = 58) with adult prisoners (Maschi & Gibson, 2012). […]

We discovered that the absence of meaning is clearly connected with the experience of distress. The fact that similar associations were found in the general population (Steger, 2012), makes our finding more robust. It also shows that prisoners are – in this aspect – not that different from the general population. Just as for people in the ‘free world’, it is essential for prisoners to make sense of their lives and to have a purpose in life. […]

Being a cross-sectional study, we were not able to search for causal relationships, or to explore the long-term implications of meaning-profiles on societal re-entry and desistance from crime. […]

Prisoners with profiles that were marked by higher levels of meaning experienced less distress, more positive world assumptions, higher levels of self-worth, and more care for others compared to prisoners with low meaning-profiles. In a way, the experience of meaning seems to buffer the daily experience of distress, as we described in the case of Martha. […]

Older prisoners and those who experienced sexual abuse during childhood were more present in the profile that was marked by lower levels of meaning and lower levels of search for meaning. Their meaning-profile seems to reflect an existential vacuum, which Frankl (1959/2006) described as a state of being marked by meaninglessness, emptiness, and apathy. People who reside in this vacuum are in extreme need of support (Frankl, 1959/2006).

Profiles of meaning and search for meaning among prisoners, Vanhooren et al, The Journal of Positive Psychology, 2016, https://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2015.1137625

Next 5 Previous 5